admin (PRO)

admin (PRO)I'd like to thank my opponent for setting up this debate. I'm blatantly going to copy my case from my previous debate on the topic.

We feel that the death penalty is unjust in nations rich and poor, anywhere in the globe. My opponent has offered the USA as a particular context, but I doubt this will be terribly relevant.

By the death penalty, we mean any system of punishment, legal or extralegal, that results, or is likely to result, in the death of the person being subjected to the punishment. We would specifically apply the death penalty in this debate, to states vested with the authority to investigate and decide crimes, especially when the death penalty is being applied in response to those crimes, as the most likely point of clash in this debate. For example, when a state executes a murderer, it is enacting a death penalty. My position in this debate is that the death penalty should never be employed.

Role of the State (background stuff)

We note that states are man-made social constructs. No divine being came down from the clouds and ordained the borders of the land we today call "India" or "Poland". Rather, these nations were created by people for human ends. Therefore the most obvious role of the state must be to serve the people. This involves aspects such as keeping people safe, and keeping people happy. Even when a state was founded with the worst of intentions, we feel this aspect holds true. ISIL, for instance, has a clear objective in the establishment of an Islamic Caliphate, but this objective is being ostensibly done according to the will of Islam, which the leaders of that movement feel would be in the best interests of people.

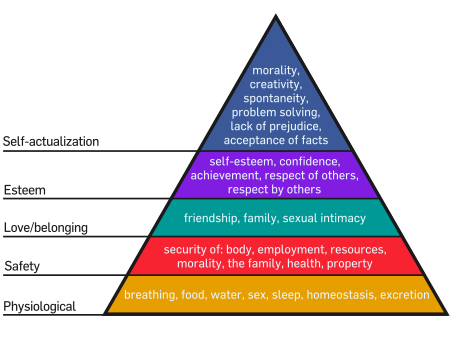

For a more objective standard on what services the people demand of the society which society creates, we feel a useful model can be found in Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Developed as a simple model for describing what kinds of things people require (and backed by clinical psychological practice), it begins with the most basic human needs, and develops towards the most advanced. The two most basic kinds of needs are safety and physiology, according to this well-established model. In general, we find that states generally provide these things for their citizens quite well under the status quo. States ensure the safety and general well-being of people by laws designed to disincentive antisocial behaviour, and by established judicial processes that ensure that these needs are being satisfied through the laws that have been passed.

When a crime has been committed, it can generally be thought of as a violation of the attempts of a state to enforce a positive society. It is also generally agreed that the punishment ought to be befitting of a crime - that is, punishments should not be made arbitrarily. These essential principles are even found in the first formal declaration of the principle of common law, hailing right back to the original version of the Magna Carta. Again, Maslow's hierarchy provides a useful framework for this, but in reverse. Less serious crimes warrant the removal of less important human needs. There can be no question, for instance, that a serious criminal should not be self-actualizing, and not hold self-esteem, because we want to send a message that these things are wrong.

It should be noted that this, like all models, is imperfect, and therefore is only useful for a generalized description of human nature. The point is largely illustrative - the state ensures lower-order needs by selectively removing higher-order needs. This is more or less how judicial systems are supposed to work, in a good state. We feel this is reinforced by the fact the most important aspect of any state is its people, so understanding psychology is fundamental to understanding this debate. Other competing models, such as fundamental human needs, follow roughly the same schema.

Human Rights

Most people would agree that something like a death pact - where multiple parties agree to kill each other - is morally abhorrent. That's because we consider that human life has a certain amount of value - an inherent dignity that suicide does not account for. A death pact fulfils all the classical requirements of a contract, but it is not generally legal because to execute it would involve committing the crime of murder. However, the same is not true of all rights. If you're travelling on a train, you cannot simply leave the train while it is in motion, but must wait for a station. Under ordinary circumstances, this would be false imprisonment - however, you hold a ticket, which is a form of contract that you agree to be imprisoned on the train until it reaches its destination. Free movement being not so fundamental a right, it is much easier to contract out of.

The notion of human rights is such that there are some rights so fundamental that a person can never contract out of, regardless of circumstance. For example, if no individual in society can justifiably agree to having themselves killed, then that society as a whole must have a right to life. The individuals in that society cannot agree to have their right removed, and therefore, it follows that any agreement reached by the members of that society (for example to form a state) must be done with reference to inviolable human rights. People receive these rights because they are human - there is no qualifier for a human right.

A state that does not respect a right that is inviolable, cannot as a matter of principle, be known as a legitimate state. For when a state loses the sanction of its people, and it no longer respects that which makes states in the first place, then that state has no moral authority to exist at all. The only question is whether the right to life, should be taken as a human right or not.

First of all, we find that this question has already been thought about for a long time, and has already a wide basis of support. The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, holds the right to life among its top priorities. The principle can be traced legally back to the precedent set by the Poljica Statute of 1444, and the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence, which famously classified the right to life as inalienable. Outside of legal theory, we find the right to life to be a valid ethical question as well, with philosophers such as Albert Camus and more recently Peter Singer raising valid objections to the point. This is to say, it is undoubtable that if any human rights exist at all, they certainly encompass the right to life. Indeed, it is this fundamental respect for life that makes a crime like murder so abhorrent in the first place. Nations around the world overwhelming support banning the death penalty, with the United Nations voting 99-52 in 2007 in favor of a ban on the death penalty on these grounds.

The goal of justice

The fact of the matter is, not just is this notion of justice insufficient, it is also perverted. Gandhi noted "An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind" - or to put it in this context, by murdering murderers, you only make more murders. Two wrongs don't make a right, even in this case. Indeed we feel that the goal of justice ought to be primarily rehabilitative, and not retributive. Since you can't reliably resurrect people from the dead (unless the court has at least a level 15 necromancer handy), courts cannot find a person worthy of the death penalty of rehabilitative grounds. In defence of this claim I'd like to advance a number of arguments.

First, we consider retributive punishment to be lacking in a working principle. We find no natural right to enact retributive justice on others, and indeed we find much of human progress has been towards enabling a society more conductive to this. Second, retributive justice has other flaws that I demonstrate throughout my case. But most crucially, rehabilitative justice does the least harm, since at least that way you have a good chance of getting at least one well-adjusted member of society in the end, rather than a bunch of dead corpses. This is no surprise - much like murder is only destructive, so too is state-sponsored murder only destructive. Fourth, we find that retributive justice is a better precedent for cases where the law is in violation of public conscience. If, say, some dictator (let's call him "Adolf") decided to invade some nation (let's call it "Poland") and made it a crime to be a citizen of that nation, then that law is clearly abhorrent. However, if the punishment is rehabilitative (Germanification) then that is less abhorrent than a retributive outcome (death by firing squad).

Finally, however, we contest that rehabilitation just simply works better. First, we find that the practical evidence demonstrates that rehabilitation has a much lower rate of re-offending than retributive crimes. Setting a precedent for retributive justice in the case of the death penalty, may therefore be harmful when trying criminals for other crimes, in that it encourages a mindset of retribution among jurors as opposed to more rehabilitative measures.

Culpability

There is also another issue. We find that in general, individuals become criminals because they are driven to that end by one or more of their human needs that they are attempting to fulfill in the context of the society they live. Murdering somebody is, of course, generally bad... but in the case of something like war, or abortion, or euthanasia, or even enacting the death penalty itself, culpability is reduced because we are acting on some other human need, as opposed to somebody who kills for no clear reason. So too is it possible that we create the social conditions for murders and other terrible crimes to occur. This is not to say that the worst of criminals should be let off the hook! Only that their culpability is inherently also mitigated by social and environmental factors, while the death penalty punishes the offender alone. It is worth noting that the death penalty is very unique in this regard. Even a long jail sentence has an attached social cost of paying for the offender's cell.

This argument has been partially copied from one of my previous essays on this topic.

When I commit a crime, the only people who really know what happened (usually) are myself, and possibly the victim (if alive). The police can only guess based on clues. It isn't surprising that they often get it wrong. Usually, the whole truth is never revealed. The problem is that with any other punishment you can correct mistakes the police make. That's called due process - you need to be able to pursue your claim of innocence after conviction, as evidence becomes available. You can't do that if you're dead. So, what if the evidence is only available after you've been executed? Take the USA for an example. Since 1973, over 150 people in over 25 states have been released from death row after they were found innocent. This proves the police get it wrong. Dozens more appear to have been executed innocently. We can never know how many were really executed innocently with any certainty, because despite their best efforts, the police can not yet time-travel.

Even if one person is innocently killed, that's too many. Any other punishment it would be alright to have innocents, but when the state kills not a killer but an innocent person, even just one, then they create guilt and multiply it upon themselves, for with the death penalty, there is no possibility of reparation for wrongs. You can't give a family a payout and expect that to replace a life, in any way. If I came to your house tomorrow, set up a sham court and convicted you to die before killing you, you would expect me to be punished. But if you replace me with the police, you would expect me to be applauded, so long as some other killers are also killed. Killing killers gives people no right to execute innocents. Since you cannot 100% prevent innocent executions, innocents will be executed cruelly and unusually for the crime of doing nothing wrong.

It is a well-known fact that in nations such as the USA, much of the probability of whether you will be convicted depends on how much the judge likes you. Judges sometimes discriminate very actively and don't always look at the facts. In the case of death penalty, where a person's life is at stake, this can have disastrous consequences. It isn't just about ethnicity. Poor people can't afford good lawyers, and so are disproportionately represented. Men are executed far more often than women. That's not fair. If we are to accept discrimination as a given - and we must, because we cannot ignore the reality of it - then we need to err on the side of caution because innocents will be convicted and killers will walk free.

This is further complicated by the procedural mess that typically accompanies the judicial right to due process when a person's very life is at stake, and the difficulty on educating a fair jury on the legal intricacies of a death penalty hearing. As Justice Cormac Carney said in an oft-quoted passage: "Inordinate and unpredictable delay has resulted in a death penalty system in which very few of the hundreds of individuals sentenced to death have been, or even will be, executed by the State. It has resulted in a system in which arbitrary factors, rather than legitimate ones like the nature of the crime or the date of the death sentence, determine whether an individual will actually be executed. And it has resulted in a system that serves no penological purpose."

Even as the number of death row inmates increases, so too does the exoneration rate, in countries with the death penalty. This indicates more miscarriages of justice are taking place, and that the system has not improved despite a long period of research on how to improve it.

The resolution is affirmed.

Return To Top | Posted:

Tejretics (CON)

Tejretics (CON)Rational choice theory -- also termed rational action theory -- is an economic theory that suggests that humans are, inherently, rational actors. This means that all humans perform a subconscious cost-benefit analysis prior to making choices [1]. It is a framework for understanding and modeling human social and economic behavior. It has been studied by economists and criminologists to see if criminals act as rationally as standard social humans. The theory has its beginnings in 1968 with the work of Gary Becker. He claimed that criminals are rational. They, like law abiding citizens, respond to costs and benefits. He argues that crime also occurs due to rationality--a cost-benefit analysis by criminals themselves [2].

Economist John R. Lott explains, “[C]riminals as a group tend to behave rationally--when crime becomes more difficult, less crime is committed.” [3] Thus, if criminals act rationally, if crime has greater costs than benefits, they likely won’t commit it. Even irrational actors can be deterred. Juveniles, who were once considered undeterrable, have actually been found to respond to arrest rates. For example, with a rise in teenage unemployment rates, they commit more thefts or other crimes. When violent crime arrests increase, juvenile violent crime rates drop [4]. People who are mentally ill respond to the price of cigarettes [5].

When it comes to the death penalty, deterrence is at work. Economists have started to spearhead death penalty research, and are increasingly taking part in the debate, since deterrence is primarily a socioeconomic factor. Economist Naci Mocan says, “Science does draw a conclusion. There is no question about it. The conclusion is [the death penalty has] a deterrent effect.” [6] There are multiple studies in favor of the death penalty’s deterrent effect.

A study by Hashem Dezhbakhsh, Paul Rubin, and Joanna Shepard found deterrence as well [10]. It is ahmong the most reliable studies in the literature, as it uses county data, instead of state data. County data is better because it is easier to control for local demographic changes, differences in arrest and conviction rates, poverty, and pretty much everything that affects murder rates. So county data should be prefered. County data, as it is a larger pool of data points, makes the conclusions more robust. The study finds that each execution deters 18 homicides. A similar estimate was calculated by John Lott, who calculated that each execution deters 15 homicides [11].

Joanna Shepard, an economist at Clemson University, uses state data from 1977 to 1999. According to her study, each death row sentence deterred, on average, 4.5 murders; each execution deterred 3 murders; one murder is deterred for every 2.75 years reduction in time spent on death row [7]. FCC economist Paul Zimmerman published two studies using state-level data, one with data from 1978 to 1997 [8], and one with data extended till 2000 [9], both finding deterrence. Other researchers agree [12][13][14][15][16].

There is a fairly strong consensus in econometric literature that the DP deters homicides. 17 studies show a deterrent effect of the death penalty, while only 5 dissent [17]. Of those five dissenting, Katz, Levitt and Shustorovich (2003) actually shows a deterrent effect [18], where the DP deters homicide rates. The reason no deterrence was found was because the study focused on the relation between the death penalty and overall crime rates, but the DP won’t deter non-homicide crimes significantly since it does not apply to assault, burglary, etc. Donohue and Wolfers published a dissenting study that is flawed since it assumes that executions happen the same year a sentence occurred [19], which is flawed since the average wait is 15 years.

Another highly reliable study is that by economists Naci Mocan and Kaj Gittings. The study analyzes a trend showing correlation between the introduction of the death penalty in various U.S. states and drop in homicide rates. It found such a correlation in Kansas, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, and New Jersey [20].

Murray Rothbard, a libertarian economist, argues “it seems indisputable that some murders would be deterred by the death penalty. Sometimes the liberal argument comes perilously close to maintaining that no punishment deters any crime — a manifestly absurd view that could easily be tested by removing all legal penalties for nonpayment of income tax and seeing if there is any reduction in the taxes paid.” [21]

Thus, the death penalty deters crime.

Preventing the repetition of murders

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that recidivism rates for homicide in the United States are quite high. 12.5% of those whose greatest offense was homicide were re-arrested in 6 months, and, over 5 years, 51.2% had been arrested again. Of those whose greatest offense was homicide, the rate was 0.9% [22]. In 2009, 8.6% of those on death row had a prior homicide conviction. Over 5% of those on death row committed their capital crime while in custody or during an escape [23]. While these numbers might seem small, they are--considering the population--quite large. In New York alone, 230 murders and rapists have been released [24]. This means a huge number of repetition, and the worst criminals--those who have committed 2 homicides--have repeated their homicides again, with 51.2% of them repeating.

An example of this is seen in Kenneth McDuff, who was placed in death row for three murders. The sentence was then commuted to life imprisonment, and was later released. Following his release, he killed 9 more people, and was then executed for this [25][26][27]. McDuff “was convicted of murdering sixteen-year-old Edna Sullivan; her boyfriend, seventeen-year-old Robert Brand; and Robert’s cousin, fifteen-year-old Mark Dunnam, who was visiting from California. They were all strangers whom McDuff abducted after noticing Sullivan; she was repeatedly raped before having her neck broken with a broomstick. McDuff was given three death sentences and subsequently convicted of having offered a bribe to a member of the parole board. He was freed in 1989. He was given a new death sentence and executed for a murder committed after his release and is suspected to have been responsible for many other killings.” [26]Lee Andrew Taylor is another example--he was sentenced to life imprisonment for killing two people--he then killed another inmate in prison [28][29].

Thus, capital punishment can save lives by preventing the deaths of multiple more people, and reducing repetition.

The death penalty is just

The death penalty offers a final touch of justice -- upholding justice and retribution by means of punishment. As Edward Feser argues, “[T]he aims of punishment are threefold: retribution, or inflicting on a wrongdoer a harm he has come to deserve because of his offense; correction, or chastising the wrongdoer for the sake of getting him to change his ways; and deterrence, discouraging others from committing the same offense.” [30]

First, I need to provide an epistemological framework for morality. When we argue about what ‘justice’ is, and what makes things ‘right’ and ‘wrong,’ we require a clear answer to this question: what is moral? Which actions can be branded as ‘moral’ and as ‘immoral’? The answer lies in respecting the rights and preferences of people. When it comes to social species such as humans, morality is respecting the dignity and autonomy of a rational actor, and respecting the idea that choices have consequences. G.W.F. Hegel observes that autonomy is what separates humans from other objects, such as chairs and tables, or of non-human species, who rely -- primarily -- on instincts, rather than choices. The axiom remains: all choices have consequences. Each criminal *knows* the consequence of each choice he makes, so retribution should be awarded for each crime, since that is the purpose of punishment [31].

Martin Perlmutter argues that “in punishment, the offender is honored as a rational being, since the punishment is looked on as his right.” [32] When I freely choose to do something, I simultaneously acquiesce to any predictable consequences that might arise therefrom. Consider a situation in a school, where students have been warned not to write on the chalkboard--if they do, they are informed that they shall be punished with a 5-minute time out. If a student does write on the chalkboard, it is reasonable they are given that five-minute time out. Similarly, the criminal who commits a horrendous crime, e.g. genocide, ethnic cleansing, or mass-murders, acquiesces to the consequence automatically--a reasonable consequence that results in deterrence and retribution. The death penalty is merely the form of punishment that is proportionate to certain crimes. Edward Feser argues, “[W]hat a wrongdoer deserves as punishment is a harm proportionate to his offense. … [T]he gravity of the punishment should reflect the gravity of the wrongdoing. Hence those guilty of large thefts should be punished more severely than those guilty of small ones, those guilty of inflicting serious bodily injury should be punished more severely than those merely guilty of theft, and so forth. … If wrongdoers do deserve punishment, and if punishment ought to be scaled to the gravity of the crime (harsher punishments for graver crimes), then it would be absurd to deny that there is a level of criminality for which capital punishment is appropriate” [30].

The desire to seek retribution has evolutionary origins. According to a study, the concept of seeking revenge has an evolutionary purpose. Science has found that the brain takes pleasure in revenge [33]. Psychologist Michael McClough argues that there is an evolutionary cause for revenge, and it merely is to have a sense of finality. According to him, the biological benefits of retribution outweigh the harms [34]. Other researchers agree [35][36][37].

Thus, the United States should not abolish the death penalty.

1.http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_R000277&q

2.http://www.nber.org/chapters/c3625.pdf

3. John R. Lott. More Guns, Less Crime, 20.

4.http://www.nber.org/papers/w7405.pdf

5.http://www.bus.lsu.edu/economics/papers/pap08_06.pdf

6.http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/06/11/AR2007061100406.html

7.https://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jlstud/v33y2004p283-321.html

8.http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/43889/2/zimmerman.pdf

9.http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=355783

10.http://cjlf.org/deathpenalty/DezRubShepDeterFinal.pdf

11. John R. Lott. Freedomnomics, 135.

12.http://aler.oxfordjournals.org/content/11/2/370.abstract

13.http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047235208000925

14.http://www.sfu.ca/~allen/deter.pdf

15.https://ideas.repec.org/p/bep/alecam/1028.html

16.http://aler.oxfordjournals.org/content/11/2/451.abstract

17.http://www.cjlf.org/deathpenalty/dpdeterrence.htm

18.http://aler.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/2/318.abstract

19.http://economics.emory.edu/home/documents/workingpapers/dezhbakhsh_07_15_paper.pdf

20. Naci Mocan and Kaj Gittings, “The Impact of Incentives on Human Behavior: Can We Make It Disappear? The Case of the Death Penalty,” (Chapter 11 in The Economics of Crime edited by Rafael Di Tella, Sebastian Edwards, and Ernesto Schargrodsky, pp. 379-418, University of Chicago Press: 2010) 394-397.

21.https://mises.org/library/libertarian-position-capital-punishment

22.http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rprts05p0510.pdf

23.http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cp09st.pdf

25.http://www.executedtoday.com/2010/11/17/1998-kenneth-allen-mcduff-texas-nightmare/

26.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenneth_McDuff

27.http://www.crimemuseum.org/crime-library/the-broomstick-killer

29.http://www.txexecutions.org/reports/469-Lee-Taylor.htm

30.http://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2011/09/4033/

31.http://tibormachan.rationalreview.com/tag/equal-rights/

32. Martin Perlmutter. “Desert and Capital Punishment.” Morality and Moral Controversies: Readings in Moral, Social, and Political Philosophy. 1981. 139-146.

33.http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-pleasure-of-revenge/

34.http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/revenge-evolution/

36. Susan Jacoby. Wild Justice: The Evolution of Revenge (New York: Harper, 1983).

37.http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/news/does-revenge-serve-an-evolutionary-purpose.html

Return To Top | Posted:

admin (PRO)

admin (PRO)I thank my opponent for his case, and would like to invite him to use the wonderful world of hotlinking (you can actually do that on edeb8) to make it significantly easier to follow his citations.

- Critical criminological theory has highlighted the class-based nature of a society where a small elite establish a law which the masses are expected to follow. It frames crimes such as homicides as acts of defiance against this social order, which people have a varying propensity to do based on the oppression they are suffering as a result of this system and their personality's propensity to act defiantly generally.

- Positivism, which broadly points out that some people might just be "born criminals." The fact is that some people are naturally violent, for instance, and thus fairly likely to be involved in an assault which might turn into a homicide. Others might be really dumb and not understand the outcomes, particularly the moral implications, of their actions. To that end, some people are literally incapable of making a rational decision to obey the law.

- Social contract criminological theory has argued that the responsibility for crime is social, not legal. To this end, a criminal act is a socially developed rejection by an individual of the social order. As such, in social contract theory, the decision to make a crime is not individual - it is both the individual and society at large, framed as a disagreement over the terms of the social contract. To be clear, criminals are just standard social humans.

- In the USA specifically, states that have no death penalty have consistently lower murder rates.

- States where the death penalty has been abolished, such as North Carolina, have generally seen a trend of decreased murder rates.

- The scientific consensus is that the question of whether murder is deterred by the death penalty in the USA is inconclusive at best. To quote from one particular meta-analysis on the topic:

"When we acknowledge that there must be instances when capital punishment

helps deter a murder, we must also recognize that at other times it can

encourage what it is meant to prevent. Since neither effect can be measured

directly we are forced back to the statistical studies, which seek to determine

the net effect. Their evidence does not prove that the death penalty is n o

added deterrent to murder, nor could it. It does show, I believe, that any

"deterrent" effect is very small in magnitude, and it might go in either

direction."

- Outside of homicide and the USA in particular, literally every shred of evidence in the world does not support the death penalty having any deterrent effect on any crime.

- Even if it did have a deterrent effect, we wouldn't consider it morally relevant. To cite the South African supreme court:

"We would be deluding ourselves if we were to believe that the execution of the few persons sentenced to death during this period, and of a comparatively few other people each year from now onwards will provide the solution to the unacceptably high rate of crime. There will always be unstable, desperate, and pathological people for whom the risk of arrest and imprisonment provides no deterrent, but there is nothing to show that a decision to carry out the death sentence would have any impact on the behaviour of such people, or that there will be more of them if imprisonment is the only sanction."

- We find exactly the same justification is relevant for the United States as well (see previous round quote).

- To make this very clear: deterrence is at best an amoral justification, and must be read as secondary to common notions of whether the death penalty is right or wrong.

"Our findings suggest that any support for the deterrence hypothesis is sensitive to the inclusion of variables for the effects of guns and other crimes... we find at best, mixed support [for the deterrence hypothesis]"

"This report shows model-averaged coefficients that fail to support the link between deterrence and capital punishment. These are the synthesis of thousands of potential specifications. Existing research on the deterrent effect of capital punishment comes to differing conclusions based upon one or more underlying assumptions that call into question the ability of any single model to explain the impact of capital punishment laws."

"...the fear [is] that a scientific paper which identifies a

deterrent effect could be taken as an endorsement or justification of the death penalty. This should not be the case for any scientific research... For example, Katz,

Levitt and Shustorovich (2003) find that the death rate among prisoners (a proxy for

prison conditions) deters crime. This finding obviously does not suggest that the society

should increase the death rate of the prisoners by worsening the prison conditions to

reduce the crime rate."

"Those who accept the death penalty on moral grounds

often seem to accept the claim of deterrence whether or not good

evidence has been provided on its behalf"

"If one assumes a priori that

individuals are incapable of calculating the risks as they are defined by [rational choice] theory, then there

is no room to conduct proper empirical research"

"Analyses of data stretching farther back in time, when there were many more executions and thus more opportunities to test the hypothesis, are far less charitable to death penalty advocates. On top of that, as we wrote in Freakonomics, if you do back-of-the-envelope calculations, it becomes clear that no rational criminal should be deterred by the death penalty, since the punishment is too distant and too unlikely to merit much attention. As such, economists who argue that the death penalty works are put in the uncomfortable position of having to argue that criminals are irrationally overreacting when they are deterred by it."

Return To Top | Posted:

Death Penalty as a form of Justice won't validate in my opinion.

Man did not create the life of man so it has no authority to decide what will it do its life.

In the killing there are an oppessor and a oppressed. It is no longer the benefit of the dead innocent but the advantage of the one who punishes.Posted 2017-12-21 14:31:24

Wow. Too bad Tej. Really enjoyed reading it, though.

I concede. I need to devote all my attention and time to my ongoing debate with Lannan, so I'm extremely sorry. Further, your arguments were pretty OP. I might have been able to refute them had I not been engaged in a tournament currently, but unfortunately... Anyway, you probably would've won the debate anyway.Posted 2015-09-19 05:50:37

@tejretics For what?

@Skepticalone - Yeah, lol. But my argument is going to be *way* longer, on account of the unlimited character limit.

@ColeTrain - Thanks!

@admin - stats master racePosted 2015-09-15 20:09:01

@admin I'm a Christian, and even I recognize that argument is inherently flawed.

This will be a good debate. Looking forward to seeing it.

This seems familiar, T! ;-)

Posted 2015-09-13 13:12:27

At least, knowing you, your rebuttals probably won't be mostly "the Bible says otherwise".Posted 2015-09-12 08:28:03

@admin - Wow I'll frame rebuttals already XDPosted 2015-09-11 03:45:20

Lol, you can expect me to re-use the case I recently ran against Krazy before he conceded the debate to me.

@admin - I hopefully will have prepared my case by then. And I hope I don't forfeit

I'll accept within a day.

@admin

Idk haven't been on Edeb8 much.Posted 2015-09-11 03:31:41

Any reason why death penalty debates seem to be popular recently? lol.Posted 2015-09-09 21:53:18